Key points

- Increasing demand and pressures on staff are taking a toll on their mental health and wellbeing. Staff have told us how, without the appropriate support, this is affecting the quality of care they deliver.

- Many people are still not receiving the safe, good quality maternity care that they deserve, with issues around leadership, staffing and communication. Ingrained inequality and the impact on people from ethnic minority groups remains a key concern.

- The quality of mental health services is an ongoing area of concern, with recruitment and retention of staff still one of the biggest challenges for this sector.

- Innovation and improvement varies, but the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in health care has the potential to bring huge improvements for people. Given the speed of growth of AI, it is important to ensure that new innovations do not entrench existing inequalities.

Current picture of quality

During 2022/23, we continued to take a risk-based approach to inspections, focusing our activity on those core services we know that, nationally, are operating with an increased level of risk, and on individual providers where our monitoring identifies safety concerns.

Our ratings data shows a mixed picture of quality, with a notable decline in maternity, mental health and ambulance services. During 2022/23, the quality of the 10 NHS trusts in England has declined, with 4 out of the 10 ambulance trusts now rated as requires improvement or inadequate. Full details our ratings for 2022/23 are available in the appendix.

Increasing demand, workforce challenges and the cost of living crisis are all having an impact on the quality of care people receive. The 2022 NHS staff survey shows a substantial decline in the proportion of staff agreeing that if a friend or relative needed treatment, they would be happy with the standard of care provided by their organisation, which at 63% is down nearly 5 percentage points since 2021. This is 11 percentage points lower than in 2020 (74%). While all types of NHS trust have deteriorated on this measure year-on-year since 2020, the decline is most marked in ambulance trusts, which have declined more than 18 percentage points since 2020, from 75% to just under 57%.

The impact of workforce wellbeing on care

Higher demand and more pressure in the health and care system is continuing to affect the health and wellbeing of staff. As we discuss in our section on workforce, 2022/23 has seen continued high levels of sickness rates for staff, with a high proportion of staff saying they felt sick as a result of work-related stress.

We have seen this in our analysis of comments from staff received through our Give feedback on care service, where they have described being under-staffed and overworked, and the negative impact this has on their wellbeing.

witnessed multiple occasions where staff raised concerns about their mental wellbeing, and were forced to continue working, or were considered to be time-wasting…I myself was signed off sick from work by my GP for poor mental health, and received no support or welfare checks from my line manager or the department.

Staff have told us how, without the appropriate support in place, stress and burnout is affecting the care being delivered. This includes, for example, staff making errors with medicines, people’s choices not being respected and people receiving worse care, or less care than they need.

The NHS staff survey shows that a third of staff said they saw errors, near misses or incidents in the last month that could have hurt staff or people using services. Ambulance staff were more likely than those in other types of trusts to have witnessed errors, with over 40% saying they had witnessed errors, near misses or incidents in the last month.

While most NHS staff (86%) said their organisation encourages them to report errors, near misses or incidents, there has been a decline in the number of staff saying they would feel safe to raise concerns. The greatest deterioration was seen in the percentage of staff who would feel secure raising concerns about unsafe clinical practice, which declined from 75% in 2021 to 72% this year. Staff who do raise concerns are also less confident that their organisation will address them.<

During this inspection, we invited clinical and non-clinical staff from all services to complete a survey [which] received 481 responses… The results showed over 50% of staff did not feel safe to report concerns without fear of what would happen as a result and did not believe that the organisation would take appropriate action. Although 43% of staff felt the trust did encourage staff to be open and honest with service users and staff when things went wrong, 35% disagreed.

From a CQC inspection report of an NHS ambulance service

Staff across all health and care sectors have used our Give feedback on care service to tell us about stress, burnout and issues with poor leadership and negative workplace cultures. Some staff have told us they feel their concerns or complaints are being ignored or even actively suppressed by leaders, as the following quotes show:

Not enough staff on the ward especially when we have a 1:1 and some patients have 2:1, which means there isn’t enough staff to do the observation or take patients out on leave. This has been spoken about and expressed by multiple [members] of staff but all the managers do is shout and say ’deal with it’…Managers aren't doing anything and they're just neglecting us.

The acute medical unit (AMU) … has had multiple near misses and serious incidents happen over the last 6 months. Senior staff raise concerns and are requested to stop email trails. [In] April a patient died in the corridor … AMU was plus 24 in the corridor across the footprint, resulting in multiple unsafe incidents. Concerns are consistently escalated.

(Quotes from Give Feedback on Care)

Issues with staffing and the resulting impact on the safety and quality of care is a theme emerging from all areas we inspect. In hospitals, despite providers’ attempts to address the issues, we have continued to raise concerns about the shortage of staff – in particular nursing and support staff – on the safety of services.

Workforce was a challenge and risk across the organisation, but in particular within the urgent and emergency care, medical and end of life services. Within the medicine core service, due to national shortages of nursing and support staff and high levels of staff absence, the service did not always have enough [of these] staff to keep patients safe. Managers of the service told us they had increased the nurse staffing establishment to allow for absences and vacancies so they could provide safe care. However, staff in the clinical areas we inspected told us they were often short of qualified nursing staff.

From a CQC inspection report

Workforce challenges are a particular concern in mental health services. Consistent staffing is fundamental to therapeutic relationships, so a high turnover of staff can have negative impact on patient recovery and lead to longer stays in hospital. We’ve also heard how a lack of staff affects services’ ability to provide therapeutic care.

A high staff turnover is also leading to skills gaps, particularly in services for autistic people and people with a learning disability. For example, in our work to understand learnings from the Supported Living Improvement Coalition, we found staff turnover resulted in the need for more training around people’s individual needs, which meant people sometimes received care from staff who did not know them well enough to support them in a person-centred way.

Through our inspections, we have also found that staff do not always have the training to carry out important assessments or reviews. As a result, we have seen delays in people receiving (or not receiving at all) higher level assessments, such as fully formulated sensory assessments, communication assessments, dysphagia assessments, functional assessment and ongoing functional analysis of behaviour. This leads to people receiving poorer quality and unsafe care. Staff also need to be able to communicate well with people to ensure the service protects their human rights.

As the demand on health and care services continues to grow, so will the stress on staff, and in turn, their ability to provide safe, effective, and person-centred care that also protects people's human rights and rights to equality. As we discuss in the section on Investing in staff wellbeing, staff have told us they need better support, which includes meeting their basic needs.

Focus on maternity services

In last year’s State of Care report we reiterated our ongoing concerns about the safety of maternity services, and the impact of poor training, poor culture and poor risk assessments on people’s care. We again stressed the inequity in maternity services and the fact that women from ethnic minority groups continue to be at higher risk.

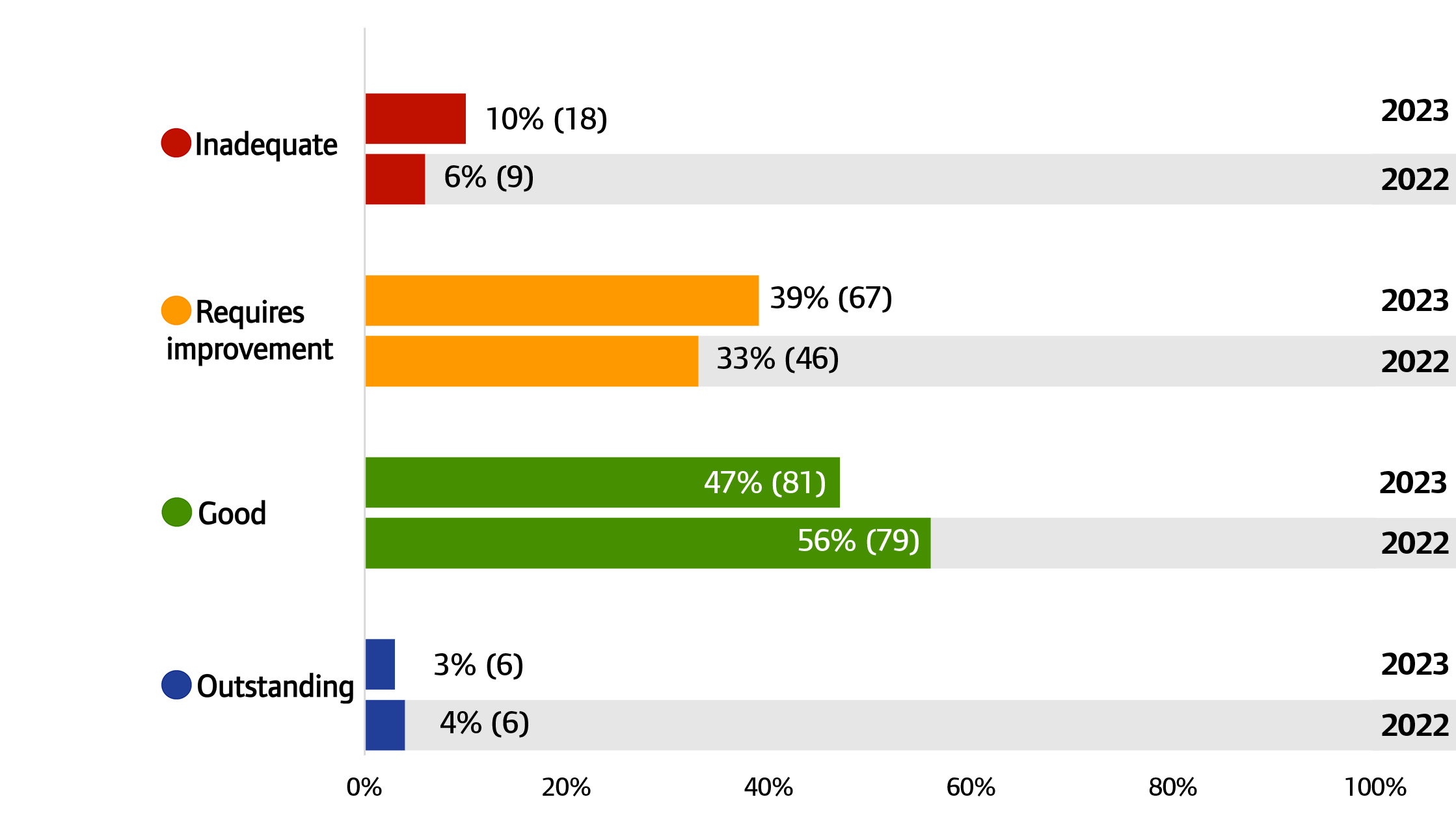

This year, we continue to have concerns around the quality of maternity services. Ten per cent of maternity services are rated as inadequate overall, while 39% are rated as requires improvement. Safety and leadership remain particular areas of concern, with 15% of services rated as inadequate for their safety and 12% rated as inadequate for being well-led.

Figure 9: Overall NHS maternity core service ratings, 2022 and 2023

Source: CQC ratings data, 31 July 2022 and 7 September 2023

Note: Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding

Over the last year, we have continued our programme of focused inspections of maternity services in NHS acute hospitals. We committed to inspecting all services that we hadn't inspected and rated since April 2021. As at September 2023, we had inspected 73% of services. The overarching picture is one of a service and staff under huge pressure. Through our Give feedback on care service, people have described staff going above and beyond for women and other people using maternity services and their families in the face of this pressure. However, many are still not receiving the safe, high-quality care that they deserve.

In the following sections, we explore some of the themes emerging from our national maternity inspection programme, including leadership, staffing and communication.

Leadership

In our report on Safety, equity and engagement in maternity services, we highlighted the importance of having a strong maternity leadership team, where the service level manager, midwifery, and obstetric leaders are all working well together to provide care that meets the needs of people using the service.

Findings from our maternity inspection programme indicate that leadership remains an area of concern, with the quality of leadership varying between trusts.

However, we have seen some good practice during our inspections, including at board level, as the following examples show.

At Hexham General Hospital, there was a clearly-defined management and leadership structure. Maternity services were led by a triumvirate, comprising the Head of Midwifery, General Manager, and Clinical Director. The Head of Midwifery was supported by 4 matrons with different responsibilities, a public health midwife and professional midwifery advocates. This team worked together, along with the rest of the trust and external agencies and bodies, to enhance the care it provides.

At the University Hospital Coventry, the trust had 3 board level champions who met with the Director of Midwifery for weekly updates regarding maternity services. They completed regular walk-arounds, and scrutinised data and reports. They were knowledgeable about the service, and proactive about holding the leadership team to account. Staff found them approachable and keen to hear their views and experiences to drive improvement.

We’ve also seen examples of trusts actively taking part in national audits, surveys, and initiatives to benchmark performance and identify areas for improvement. Where local leaders have clear board-level oversight, scrutiny and support, services are empowered to improve.

However, we have still found issues with governance and lack of oversight from boards, including challenges in identifying issues and packages of support at service delivery level. We also have concerns about problematic working relationships between service level managers, neonatal, midwifery and obstetric leaders.

To address these leadership concerns and develop a positive safety culture, NHS England’s Three year delivery plan for maternity and neonatal services includes a commitment that all neonatal, obstetric, midwifery and operational leads will have been offered the perinatal culture and leadership programme by April 2024. This includes a diagnosis of local culture and practical support to nurture culture and leadership.

Staffing issues

As well as difficult working relationships, staffing remains a key challenge for many leadership teams. Through our inspections we have seen examples of significant staffing issues in many of the trusts we have visited. Issues include high vacancy rates and staffing levels that fell below the recommended workforce numbers for full time equivalent midwives, as well as gaps in leadership teams themselves. In some cases, staffing shortfalls have led to the closure of birthing suites, or women and other people using maternity services being sent to other hospitals to give birth.

In our July blog about our programme of focused inspections, we highlighted our specific concerns around obstetric consultant cover for maternity units. While we were encouraged that the majority of units were meeting the recommendations of the Ockenden report, we highlighted that the cover model is often fragile, with the rotas relying on every consultant being available. On top of this, consultants face additional pressure from, for example, having to cover registrar rotas and extra on-call shifts to meet the needs of their service.

Issues with staffing and the impact on patient care was a theme emerging from our analysis of comments received through our Give feedback on care service, with many people describing staff as overstretched and overworked. This is supported by findings from the NHS staff survey, which showed that only 20% of midwives would say that they are able to meet all the conflicting demands on their time at work.

Not having enough staff can lead to delays in care and, in some cases, people not receiving one-to-one care during labour. In one extreme example, the lack of staffing resulted in inadequate home birthing support options and led to one woman giving birth unaided in a birthing pool at home.

The impact of staff shortages on care after giving birth was also evident in comments received through our Give feedback on care service. While people appreciated that maternity staff were often doing their best despite being very busy, many described feeling that they were not a priority and did not get the help they needed, as the following feedback shows:

I couldn’t move and asked someone to help me feed my baby and was told ‘you can do it yourself’ … [The midwife] also told me that she was very busy and had other patients that took priority – when I still couldn’t move.

I did understand that the midwives were busy and the induction patients were a more urgent priority, but I did very much feel like I was of no importance and they didn’t see me as ‘their’ patient. At this point I’d had surgery to have my daughter at 29 weeks and was very tired, stressed and overwhelmed and only 2 midwives in the 10 or 15 I had were empathetic and properly took time to care for me and help me.

Despite these challenges, we are seeing examples where services are taking action to manage staff levels safely. For example, one service consistently used policies on escalation and closure to keep senior managers and clinicians informed and involved during busy periods. This included having arrangements embedded to call on trained general nursing staff to support with care that was not midwifery-specific, such as providing post-surgical care.

Communication

Effective communication is essential to ensuring that women and other people using maternity services are engaged in their care. It also supports shared decision-making. NICE guidanceon antenatal care sets out several principles for effective communication. This includes providing clear, understandable and timely information that considers people’s individual needs and preferences.

From the initial findings of our inspection programme, we are concerned that poor communication is affecting the quality of care for women and other people using maternity services. This is supported by the findings of the 2022 maternity survey, which showed that just 59% of women and other people using maternity services said they were always given the information and explanations they needed during their care in hospital.

Looking at more detailed responses to the maternity survey, we found many accounts of women and other people using maternity services feeling they were not being listened to, and their choice being taken away due to poor communication and information. In some cases, we found that people were not receiving key information relating to the care of themselves or their baby, as these quotes from the survey show:

There was a lot of miscommunication and lack of recording and documentation of my personal circumstance, which resulted in less overall effective care.

I do not feel I was given enough information about jaundice and the impact that it was having on my baby’s feeding, whilst on the postnatal ward. Communication about how much and how often my baby needed to feed was conflicting, which made me worry that I was somehow making the jaundice worse.

This echoes findings from recent research from Healthwatch, where new mothers were interviewed about their experiences. A key concern for the mothers was around miscommunication about their care. They told Healthwatch that this meant they didn’t have the opportunity to make their needs heard, and that sometimes they didn’t fully understand the care options they were consenting to.

In services where we have seen good practice, information has been available in different formats to cater for a range of needs and empower people to make informed choices about their care. For example, one trust used personalised care guidelines to keep staff focused on providing individualised care. Women and other people using maternity services were offered genuine choice, informed by unbiased information.

But it is not just about ensuring people have the information they need. The way in which staff communicate can also have a huge impact on their experience. Many comments received through Give feedback on care referred to midwives as being friendly, reassuring, comforting and helpful. Many people also felt that midwives treated them with genuine care, offering a listening ear at times of difficulty and taking the time to make them feel supported and confident.

However, we also found several instances of people describing negative staff interactions, noting staff in general as often being rude and unhelpful, discouraging, inconsiderate of individuals’ feelings, patronising and unsupportive. A few people noted the lack of empathy and bedside manner of midwives and consultants, identifying these interactions as unnecessarily upsetting:

The midwives on the ward were horrendous. They were rude, condescending and made me cry on a daily basis.

Midwives and staff need to be refreshed on empathy, compassion, support. I appreciate hundreds of women give birth every day, but each one of those women is an individual going through their own journey and should be treated as such.

(Quotes from Give feedback on care)

Impact of inequalities on maternity care

Despite multiple reviews, reports and recommendations on maternity care, a lot of the issues we are finding through our national maternity inspection programme are not new.

Some women and other people using maternity services face inherent inequalities. As we highlighted in last year’s State of Care, women from ethnic minority groups continue to experience additional risks compared with women in White ethnic groups that – without the right interventions – can lead to poor outcomes.

In its August 2023 QualityWatch report on Stillbirths and neonatal and infant mortality, the Nuffield Trust highlighted that in 2021, the infant mortality rate among Black ethnic groups was substantially higher than any other groups, with 6.6 deaths per 1,000 live births. Asian ethnic groups had the second highest infant mortality rate at 4.8 deaths per 1,000 live births. By comparison, White ethnic groups consistently had the lowest infant mortality rates with 3 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2021.

During 2022, re-admission rates of Black women during the 6-week postpartum period have continued to rise, and are still significantly higher than re-admission rates for women of other ethnicities (figure 10).

Figure 10: Rate of re-admissions per 1,000 deliveries during the postpartum period by quarter, January 2019 to December 2022

Source: Hospital Episode Statistics

We wanted to understand more about inequalities in maternity care for people from ethnic minority groups. To do this, in July this year we commissioned a small, bespoke piece of research interviewing midwives from ethnic minority groups about:

- their own personal experiences of working in maternity services

- their insights into the experiences of people from ethnic minority groups who were using maternity services, and related safety issues.

Full findings from the research are detailed in the section on Inequalities.

Quality of mental health care

Access to mental health care and the quality of the care remain a key area of concern. As we reported in last year’s Monitoring the Mental Health Act report, unavailability of community care continues to put pressure on mental health inpatient services, with many services struggling to provide a bed. In turn, this is leading to people being cared for in inappropriate environments.

A recent report from the National Audit Office highlighted that an estimated 8 million people with mental health needs are not in contact with NHS mental health services. Some people in need of help are facing lengthy waits for treatment. As at June 2022, an estimated 1.2 million people were on the waiting list for community-based NHS mental health services. This is despite more funding and increasing staffing levels for mental health services, and more patients being treated.

In 2022, NHS England set out its proposals for new mental health waiting time standards. These included proposals that people who need non-urgent mental health care from community-based mental health services should wait no more than 4 weeks after being referred.

Not getting the help they need, when they need it can lead to people reaching crisis point and seeking help from, for example, urgent and emergency care. This is a particular concern for children and young people.

In May 2023, the Community Network published the results of its survey of 67 community provider leaders. Respondents were from trusts (accounting for nearly two-thirds of the sector) and community interest companies. Results show that despite the best efforts of community providers, there are still concerning waits for services for children and young people, which has a significant impact on children and families, and on staff morale. Respondents particularly highlighted the impact on those children presenting with more complex or specialist needs. They said that deterioration in conditions over time could lead to increased needs when the child is seen, as well as more children presenting at emergency departments or in crisis.

This is supported by a 2022 survey of nearly 14,000 young people aged 25 and under by YoungMinds. While not nationally representative, the results showed that 58% of young people who tried to get mental health support said their mental health got worse during their wait, with over a quarter (26%) saying they had tried to take their own life.

The lack of mental health beds means that people are then facing lengthy waits in an emergency department while they wait for a mental health bed to become available.

In one trust, we saw evidence of a significant number of mental health patients waiting for long periods in cubicles until appropriate mental health inpatient beds became available. We found this was a significant issue of concern, as 42 people were waiting more than 36 hours in the emergency department in October alone. The trust subsequently provided data to show that during October and November 2022, it had the equivalent of 10 [emergency department] cubicles full of mental health patients.

From a CQC inspection report

As well as long waits, people are often facing the prospect of being sent far from home for care and treatment. Despite a government commitment to ending out of area placements, as at May 2023, there were 775 out-of-area placements across England. As we have highlighted in our other reports, placing people in hospitals far from home and away from friends, family and support networks can affect their recovery and increase the risk of a closed culture developing.

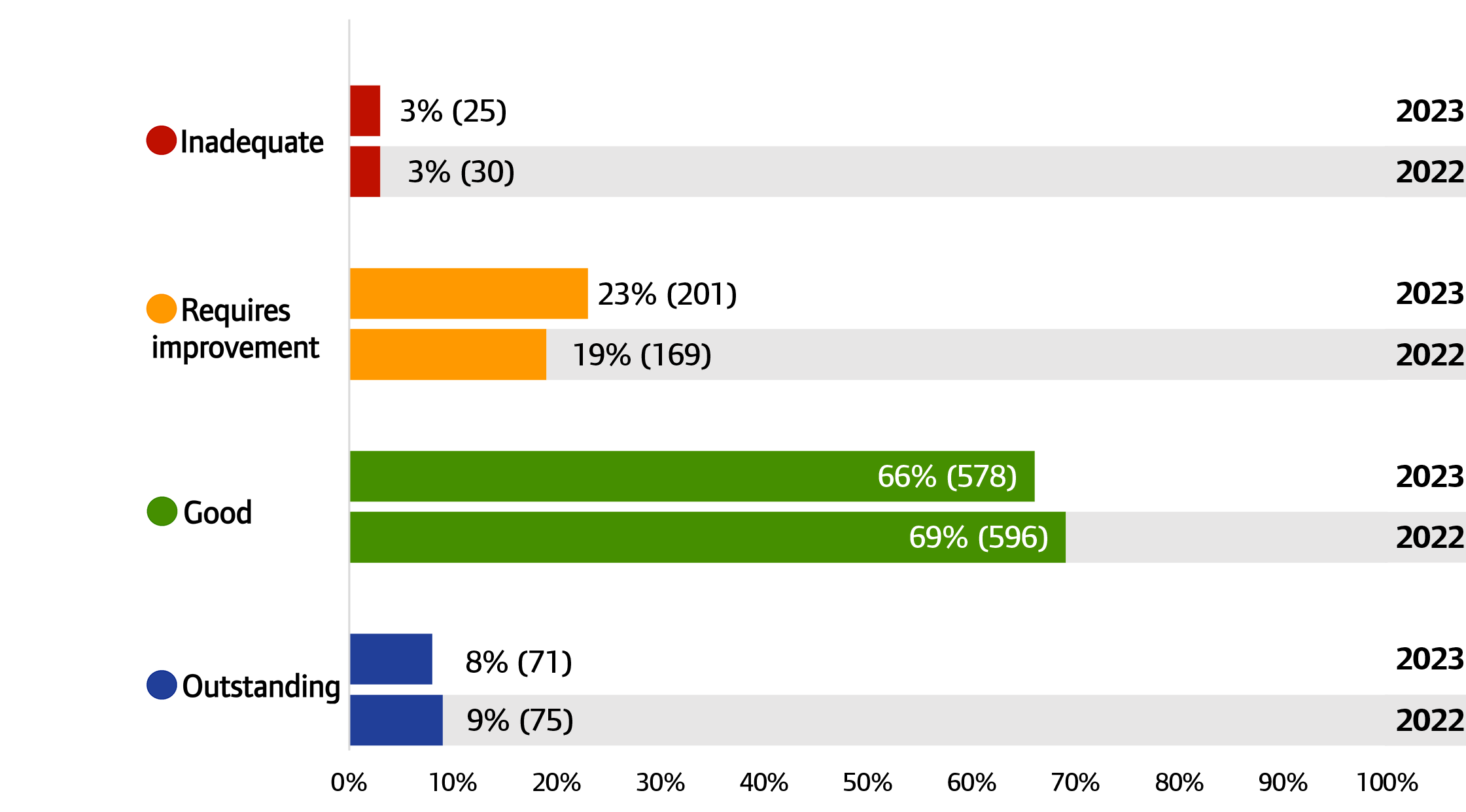

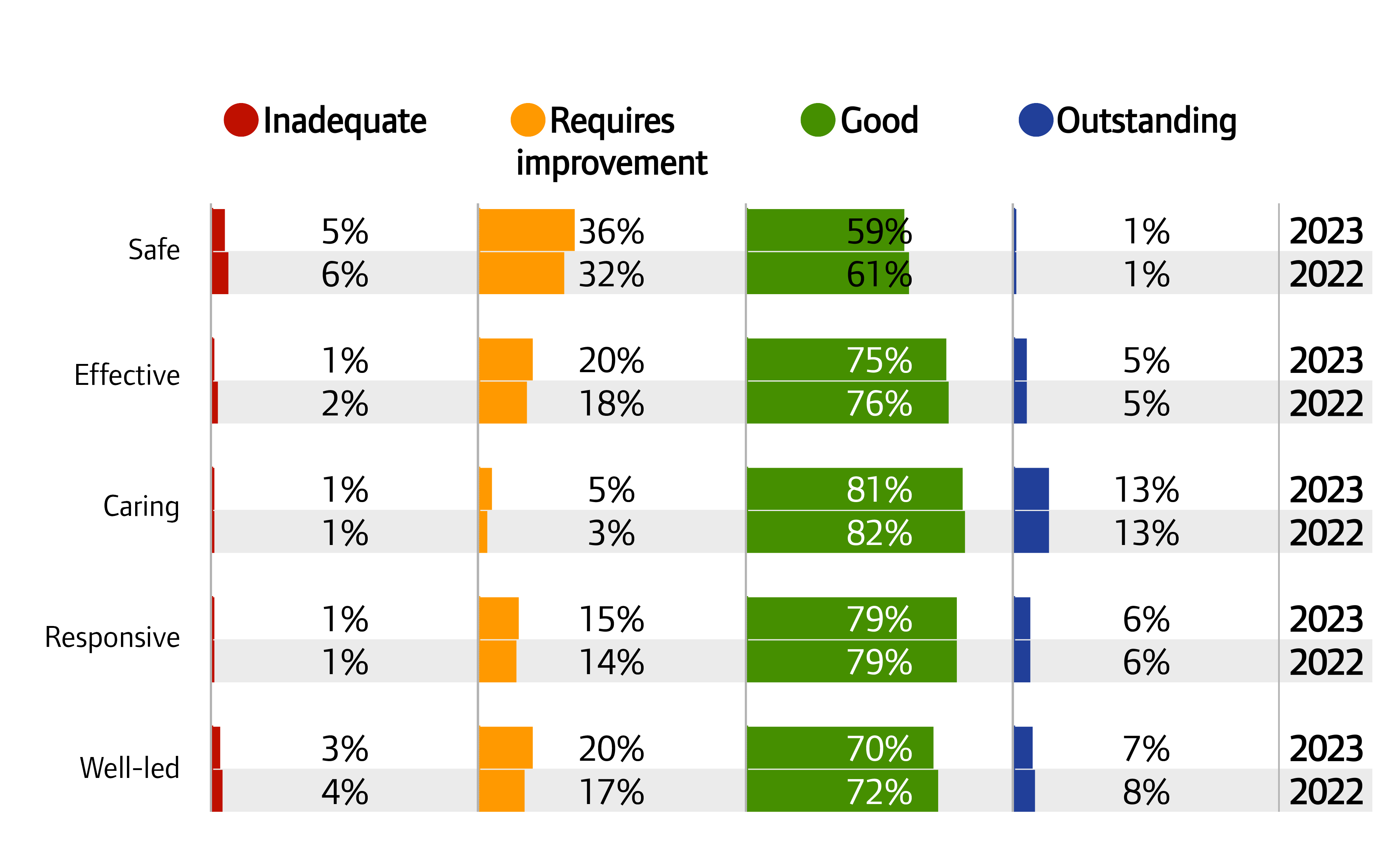

When people do get a bed in a mental health hospital, the quality of care is still not good enough, with areas of concern including the use of dormitories and mixed sex wards. Using our risk-based approach to inspection, our ratings data shows a slight decrease in the proportion of providers rated as good. At a key question level, the safety of services continues to be an area of concern, with 40% rated as requires improvement or inadequate (figures 11 and 12).

Figure 11: NHS and independent mental health services overall ratings, 2022 and 2023

Source: CQC ratings data, 31 July 2022 and 7 September 2023

Note: Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding. Percentages between 0.01% and 1% have been rounded up to 1%.

Figure 12: NHS and independent mental health services key question ratings, 2022 and 2023

Source: CQC ratings data, 31 July 2022 and 7 September 2023

Note: Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding. Percentages between 0.01% and 1% have been rounded up to 1%.

Staffing challenges

Recruitment and retention of staff remains one of the biggest challenges for mental health services, with the use of bank and agency staff higher than ever. This is supported by data from NHS England, which shows that, in the first 3 months of 2022/23, almost 1 in 5 mental health nursing posts were vacant.

The use of agency staff puts pressure on permanent staff and increases risk to people using services, as staff do not always know them. For example, we visited one hospital where there were 7 permanent staff and 6 agency staff on one shift caring for 12 patients. The role for all the agency staff was to escort patients to home or to health appointments, but they did not necessarily even know the patient and their needs.

Where the quality of care does not meet the fundamental standards or where there’s a need for significant improvement, we can issue a Warning Notice. In the last year, we issued Warning Notices to NHS and independent mental health care providers because of staffing issues including:

- not having enough registered nurses

- poor mandatory training figures

- poor records management.

For example, we served one trust with 4 Warning Notices to make sure it addressed significant concerns, including staffing. This trust had high levels of vacancies, which meant people were often treated by temporary staff who were unfamiliar with their needs. We also found that staff did not always follow the trust’s policies and procedures on reporting and recording incidents.

When following up a Warning Notice at a different service, again we were concerned to find it did not have enough appropriately skilled staff to meet people’s needs and keep them safe. There was only one full-time nurse and the service was overly reliant on bank and agency staff, especially at evenings and weekends, who didn’t understand people’s individual needs.

We are particularly concerned about longstanding issues with staffing at all 3 of England’s high secure hospitals. These specialist psychiatric hospitals provide care for people with mental illness and personality disorders who represent a high degree of harm to themselves or others./p>

At the time of each inspection, all 3 high secure hospitals continued to have a significant shortage of staff, particularly registered nurses. Challenges with staffing significantly restrict patients’ access to therapies and activities. This is often because staff delivering therapy or activities are used to cover for general nursing staff or other staff shortages, or in some cases, because there are not enough staff to escort patients to the relevant activity areas.

We have written to the leaders of all 3 high secure hospitals with our expectations that they consider people’s individual circumstances when making decisions about night-time confinement. We have often seen blanket restrictions applying to everyone on the ward, which rarely consider the clinical and psychosocial grounds for reviewing confinement. Limitations on activities and blanket restrictions will inevitably have a negative impact on people’s recovery.

Reducing restrictive practices

Time and again we have heard about the devastating impact of the use of restrictive practices on people receiving care and the trauma they experience as a result. Earlier this year, we developed a new policy position on reducing restrictive practice.

While we recognise that using restrictive practices may be appropriate in limited, legally justified and ethically sound circumstances, our policy is clear that its use should be rare and could be seen as a failure of care. It sets out our expectations for everyone working in health and social care and includes the expectation that providers understand the events that led up to restrictive practice being used. They must also report on the use of restrictive practices, learn from them, and actively work to reduce them in future.

Focus on risks with medicines

As the regulator, we are responsible for making sure that providers, and other regulators in England, maintain a safe environment for the management and use of controlled drugs. These commonly used medicines are subject to additional legal controls as they carry a higher risk of being misused or causing harm.

Our work spans NHS and independent services in both health and adult social care, and we work closely with NHS England in this area.

During our inspections in 2022, we have found good and poor practice in how controlled drugs are managed and used.

An area of concern in relation to medicines is where care is shared between NHS providers and independent or private services. Examples include concerns such as evidence of clinicians prescribing controlled drugs to patients without the relevant medical and medication history. We have seen examples where private prescribing services have not requested these details from the person’s NHS GP or secondary care provider before issuing prescriptions, as well as examples of GP services that don’t supply these details in an appropriate way when asked.

Shared care can be ineffective when medicines licensed for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are prescribed privately, as monitoring patients is a key concern, especially when they need tests at certain intervals. Private prescribing of Schedule 2 controlled drugs overall increased by 80% between 2021 and 2022, which was largely driven by the increase in prescribing for medicines licensed for ADHD.

Another current issue is prescribing controlled drugs in instalments, which is currently only available on paper prescriptions. There is a real need to move this to electronic format through the Electronic Prescription Service. This would help to prevent avoidable harm and provide more seamless care for patients by avoiding delays or missed doses of medicines if prescriptions have been lost, delayed in transit, or as a result of miscommunication between different care providers.

We have previously raised concerns about over-prescribing medicines that cause dependence and withdrawal. These include opioid medicines for pain, the gabapentinoids, benzodiazepines and Z-drugs (medicines that act in a similar way to benzodiazepines), and antidepressants.

Better awareness and initiatives to address this type of prescribing will improve patient outcomes in NHS GP services. In March 2023, NHS England released a Framework for action for integrated care boards (ICBs) and primary care to help support this ongoing priority. Actions at integrated care system (ICS) level have the potential to provide leadership and improve local collaboration to benefit patients. Over the last year, we have heard about examples of this good work, including:

- A range of opioid reduction projects in the North East that include a campaign aimed at helping GP practices to review opioid prescribing in primary care. This includes videos of patients’ lived experiences.

- The 'Living well with pain' programme in Gloucestershire, which uses a system-wide approach to help bring services together for effective patient care. This is an evidence-based programme, focused on exercise and improved access to mental health services, to help people with chronic pain live as well as possible.

It’s not just healthcare services that handle controlled drugs. Each year, we ask registered adult social care providers to provide information about whether they administer controlled drugs, and if so, how many controlled drug-related medicines errors occurred in the service in the previous 12 months.

Of the providers that responded:

- 67% (13,501) of services (20,184) said they administered controlled drugs

- of the services that administer controlled drugs, 17% (2,248) reported controlled drugs incidents in the previous 12 months

- 39% (7,846) of services (20,122) reported no medicines errors at all.

Staff need to feel supported to be open about reporting errors and to learn from them. This is crucial to reduce the risk of a similar event happening again.

During some of our inspections of adult social care services in 2022, we found examples of good awareness of the principles and application of STOMP guidance (stopping over-medication of people with a learning disability, autism or both). Some medicines that STOMP guidance refers to are controlled drugs, such as benzodiazepines or Z-drugs.

One of the key aspects of this guidance is ensuring that prescribing and administration of these medicines is appropriate and, where possible, that non-drug options are available so these medicines are not used to control people’s behaviour.

The pandemic brought into sharp focus the challenges associated with managing pain and relieving symptoms for people at the end of their lives. We hear from care home providers about the cost and lengthy process associated with obtaining a Home Office licence to hold a very small quantity of controlled drugs as anticipatory medicines. In practice, this means that many care homes don’t hold any stock, so they need to use other routes to prescribe and supply controlled drugs to ensure that patients can access these medicines.

We know there is a great deal of excellent work in relation to anticipatory prescribing to ensure that people get the medicines they need at the right time. However, it is sometimes difficult to predict when a patient might be nearing the end of their life, which can mean the right medicines are unavailable both within the care home setting and when people choose to die at home.

In some cases, delays to treatment and additional work can be caused by issues such as:

- incorrectly written prescriptions or authorisations to administer

- unavailability of stock

- access to medicines out of normal hours.

This is especially relevant given the ongoing pressures on health and care staff after the pandemic.

Medicines optimisation in virtual wards

Virtual wards (also known as ‘hospital at home’) allow people to get hospital-level care at home in familiar surroundings, including care homes. According to The British Geriatric Society, the benefits of virtual wards, particularly for older people, include preventing delirium, falls and hospital acquired infections.

They are a key priority for NHS England to help increase capacity across the system. By December 2023, integrated care systems are expected to have developed virtual wards towards a national ambition of 40 to 50 virtual beds per 100,000 population.

NHS England published a series of case studies on virtual wards, which demonstrate their advantages in supporting people to get better in their own homes. For example, in one case study, a care home reported that fewer people attended the emergency department and it was able to treat people holistically, improving their clinical and wellbeing outcomes.

Most people admitted to virtual wards are taking medicines. To understand the best ways to use medicines in these settings, our Medicines Optimisation team held discussions with acute and community health providers and other key stakeholders between December 2022 and March 2023. Providers told us about concerns as well as good practice, and how CQC can work with them to drive improvement in this area. We identified some key themes.

Workforce and governance

Often, pharmacy teams were not involved in setting up a virtual ward from the outset, so they had no influence in decisions on the use and supply of medicines. Sometimes there was no allocated budget for pharmacy staffing, which meant leadership often fell to a trust’s chief pharmacist without any additional resource, resulting in policy, practice, and governance of medicines being overlooked.

One provider addressed this by using existing pharmacy staff in primary care networks and community pharmacists to support the virtual ward, which also improved continuity of care.

Stakeholders voiced their concerns over which medicines guidance and formularies virtual wards should use. Medicines such as antimicrobials and those for end of life care must be prescribed correctly for optimal patient outcomes. Leadership accountability needed to be clearly defined, particularly where multiple providers are involved.

Use of technology and digital systems

A lack of integration and compatibility between digital systems in acute, community trusts and primary care made transferring information challenging. Prescribing and recording medicines administration, including when people were self-administering their medicines, presented additional digital challenges.

One trust used a smart phone messaging facility to enable patients to contact staff if there were problems with their medicines and their supply was low.

Storage and supply of medicines

Challenges include storing medicines securely and assessing and mitigating these risks, as well as being clear around the accountability of medicines stored in people’s own homes. Transporting medicines to people’s homes could also be difficult and different providers used various ways to supply medicines to people. One trust had identified community pharmacies that opened late so they could direct late prescription requests to them when needed. But the problem remained when people needed medicines that could only be supplied by the hospital.

Virtual wards and health inequalities

NHS England’s supporting information for ICS leads outlines the positive impact of virtual wards on health inequalities by broadening equity of access and optimal care in people’s own homes, although it is important to avoid digital exclusion.

Providers felt it would be useful to review admission criteria to identify and mitigate any geographical inequalities in access. It’s also important to consider individual needs when interacting with people on virtual wards, for example where English is not a first language or for people with no access to technology.

Collaborative working, improvement and shared learning: To improve medicines optimisation in virtual wards, providers identified the need for leaders to collaborate and share learning across systems, and to involve pharmacy teams from the start. We are continuing to collaborate with stakeholders and providers to drive improvements in this type of setting.

Innovation and improving care

Innovative practice and technological change are important tools to drive improvement and deliver better outcomes and experiences for people. This might be through digital technologies, but it can also mean new ways of working or new care models that improve their outcomes.

One of our strategic ambitions is to accelerate improvement in health and care. We want to use our unique position to support health and care services, and local systems, improve how they deliver good care for people, and to identify and address their own challenges. A key part of this is encouraging innovative practice and technological changes where they benefit people.

Over the last year, we have carried out work funded by the Regulators’ Pioneer Fund. Through this, we have heard anecdotally how staffing pressures and strains on resources are hindering innovation. As we highlight in the challenges facing adult social care services, a lack of support and investment from integrated care systems can have a negative impact on the ability of providers to re-invest in their services and improve care for people.

With these pressures, there is the risk that innovations may be focused on improving efficiencies for the health and social care system, rather than driving better quality care for people. Innovation must focus on the individual people receiving care, and must be at the heart of designing and measuring the outcomes of an innovation.

It has been encouraging to see evidence of providers using innovation – both technology and non-technology driven – to improve the quality of care in the face of these challenges.

Example of using AI to improve care

Staff at one care home were noticing that large quantities of antipsychotic medicines were being prescribed for people with dementia. When people were distressed and were communicating this through behaviour, there appeared to be little consideration of the reasons why, and so they were given antipsychotics in response. But staff were convinced that these distress responses were a reaction to pain – not because the person had a diagnosis of dementia.

The care home therefore worked with developers to pilot a new app that used artificial intelligence (AI) technology to help care staff identify when people were in pain. The app helps the caregiver to recognise and record facial muscle movements and identify other behaviours that indicate pain. It then calculates an overall pain score and stores the result.

After it was introduced in 2021, the care home has not only been able to offer more pain relief to people, but there have been fewer conflict-related safeguarding referrals and more time available for staff. Importantly, there has also been a 10% decrease in antipsychotic medicine use across all 23 homes. This has improved the quality of life for people with dementia.

The use of AI in health care has the potential to bring huge improvements for people using services. However, given the speed of growth, it’s important to ensure that new innovations do not embed existing inequalities. These can occur at different stages of AI development, for example bias at the design and development stage. Everyone involved in bringing new technology to care must take responsibility for making sure that innovations reduce inequalities. This includes a role for developers working on these products, but also for providers that adopt them to monitor outcomes and implement robust governance and evaluation of the changes.

To ensure that people benefit from AI, health and care providers also need to ensure that staff are properly trained to use it. The recent Health Education England and NHS AI Lab report found that if people receiving care are to benefit from AI, healthcare workers will need specialised support to use AI safely and effectively as part of clinical reasoning and decision-making.

As the regulator, we’re also considering the role we play as AI becomes more widespread in health and care. Along with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, and the Health Research Authority, we form part of the AI and digital regulations service. This is a cross-regulatory advisory service that supports developers and adopters of AI and digital technologies. The service provides guidance across the regulatory, evaluation and data governance pathways.

While innovation such as the use of AI is important, it's just one tool to support improvement. We recognise that it is not only providers rated as outstanding or good that innovate. Innovation does not always look the same and can include, for example, advances in digital technology, new models of care and new ways to treat, monitor and care for people. Innovation is not a one-off activity and requires a culture that supports both innovation and improvement to thrive.